Hacking WeasyPrint¶

Assuming you already have the dependencies, install the development version of WeasyPrint:

git clone git://github.com/Kozea/WeasyPrint.git

cd WeasyPrint

python3 -m venv env

. env/bin/activate

pip install -e .[doc,test]

weasyprint --help

This will install WeasyPrint in “editable” mode (which means that you don’t need to re-install it every time you make a change in the source code) as well as pytest and Sphinx.

Lastly, in order to pass unit tests, your system must have as default font any font with a condensed variant (i.e. DejaVu) - typically installable via your distro’s packaging system.

Documentation changes¶

The documentation lives in the docs directory,

but API section references docstrings in the source code.

Run python setup.py build_sphinx to rebuild the documentation

and get the output in docs/_build/html.

The website version is updated automatically when we push to master on GitHub.

Code changes¶

Use the python setup.py test command from the WeasyPrint directory to

run the test suite.

Please report any bugs/feature requests and submit patches/pull requests on Github.

Dive into the source¶

The rest of this document is a high-level overview of WeasyPrint’s source code. For more details, see the various docstrings or even the code itself. When in doubt, feel free to ask!

Much like in web browsers, the rendering of a document in WeasyPrint goes like this:

The HTML document is fetched and parsed into a tree of elements (like DOM).

CSS stylesheets (either found in the HTML or supplied by the user) are fetched and parsed.

The stylesheets are applied to the DOM-like tree.

The DOM-like tree with styles is transformed into a formatting structure made of rectangular boxes.

These boxes are laid-out with fixed dimensions and position onto pages.

For each page, the boxes are re-ordered to observe stacking rules, and are drawn on a PDF page.

Cairo’s PDF is modified to add metadata such as attachments, embedded files, and PDF trim and bleed boxes.

HTML¶

Not much to see here. The weasyprint.HTML class handles step 1 and

gives a tree of HTML elements. Although the actual API is different, this

tree is conceptually the same as what web browsers call the DOM.

CSS¶

As with HTML, CSS stylesheets are parsed in the weasyprint.CSS class

with an external library, tinycss2.

In addition to the actual parsing, the weasyprint.css and

weasyprint.css.validation modules do some pre-processing:

Unknown and unsupported declarations are ignored with warnings. Remaining property values are parsed in a property-specific way from raw tinycss2 tokens into a higher-level form.

Shorthand properties are expanded. For example,

marginbecomesmargin-top,margin-right,margin-bottomandmargin-left.Hyphens in property names are replaced by underscores (

margin-topbecomesmargin_top). This transformation is safe since none of the known (not ignored) properties have an underscore character.Selectors are pre-compiled with cssselect2.

The cascade¶

After that and still in the weasyprint.css package, the cascade

(that’s the C in CSS!) applies the stylesheets to the element tree.

Selectors associate property declarations to elements. In case of conflicting

declarations (different values for the same property on the same element),

the one with the highest weight wins. Weights are based on the stylesheet’s

origin, !important markers, selector

specificity and source order. Missing values are filled in through

inheritance (from the parent element) or the property’s initial value,

so that every element has a specified value for every property.

These specified values are turned into computed values in the

weasyprint.css.computed_values module. Keywords and lengths in various

units are converted to pixels, etc. At this point the value for some

properties can be represented by a single number or string, but some require

more complex objects. For example, a Dimension object can be either

an absolute length or a percentage.

The final result of the get_all_computed_styles()

function is a big dict where keys are (element, pseudo_element_type)

tuples, and keys are style dict objects. Elements are ElementTree elements,

while the type of pseudo-element is a string for eg. ::first-line

selectors, or None for “normal” elements. Style dict objects are dicts

mapping property names to the computed values. (The return value is not the

dict itself, but a convenience style_for() function for accessing it.)

Formatting structure¶

The visual formatting model explains how elements (from the ElementTree tree) generate boxes (in the formatting structure). This is step 4 above. Boxes may have children and thus form a tree, much like elements. This tree is generally close but not identical to the ElementTree tree: some elements generate more than one box or none.

Boxes are of a lot of different kinds. For example you should not confuse

block-level boxes and block containers, though block boxes are both.

The weasyprint.formatting_structure.boxes module has a whole hierarchy

of classes to represent all these boxes. We won’t go into the details here,

see the module and class docstrings.

The weasyprint.formatting_structure.build module takes an ElementTree

tree with associated computed styles, and builds a formatting structure. It

generates the right boxes for each element and ensures they conform to the

models rules (eg. an inline box can not contain a block). Each box has a

style attribute containing the style dict of computed values.

The main logic is based on the display property, but it can be overridden

for some elements by adding a handler in the weasyprint.html module.

This is how <img> and <td colspan=3> are currently implemented,

for example.

This module is rather short as most of HTML is defined in CSS rather than in Python, in the user agent stylesheet.

The build_formatting_structure()

function returns the box for the root element (and, through its

children attribute, the whole tree).

Layout¶

Step 5 is the layout. You could say the everything else is glue code and this is where the magic happens.

During the layout the document’s content is, well, laid out on pages. This is when we decide where to do line breaks and page breaks. If a break happens inside of a box, that box is split into two (or more) boxes in the layout result.

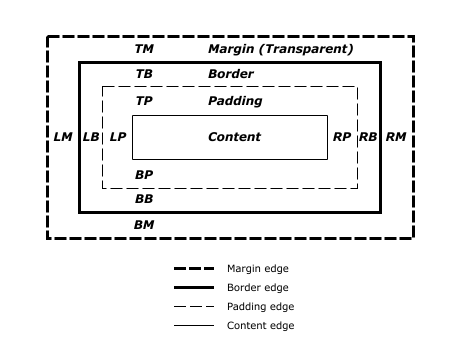

According to the box model, each box has rectangular margin, border, padding and content areas:

While box.style contains computed values, the used values are set

as attributes of the Box object itself during the layout. This

include resolving percentages and especially auto values into absolute,

pixel lengths. Once the layout done, each box has used values for

margins, border width, padding of each four sides, as well as the

width and height of the content area. They also have

position_x and position_y, the absolute coordinates of the

top-left corner of the margin box (not the content box) from the top-left

corner of the page.1

Boxes also have helpers methods such as content_box_y() and

margin_width() that give other metrics that can be useful in various

parts of the code.

The final result of the layout is a list of PageBox objects.

- 1

These are the coordinates if no CSS transform applies. Transforms change the actual location of boxes, but they are applied later during drawing and do not affect layout.

Stacking & Drawing¶

In step 6, the boxes are reordered by the weasyprint.stacking module

to observe stacking rules such as the z-index property.

The result is a tree of stacking contexts.

Next, each laid-out page is drawn onto a cairo surface. Since each box has absolute coordinates on the page from the layout step, the logic here should be minimal. If you find yourself adding a lot of logic here, maybe it should go in the layout or stacking instead.

The code lives in the weasyprint.draw module.

Metadata¶

Finally (step 7), the weasyprint.pdf module parses (if needed) the PDF

file produced by cairo and adds metadata that cannot be added by cairo:

attachments, embedded files, trim box and bleed box.